Just over the road from the Royal Academy, Margaret Thatcher’s Spitting Image puppet leers out of an arresting window display. The former prime minister is there to welcome visitors to the Center for British Photography, an intriguing new art space that has just opened up on Jermyn Street alongside quintessentially British brands like Paxton & Whitfield (cheese) and Hawes & Curtis (suits).

Across the doorway from Peter Fluck and Roger Law’s creation of foam, another display shows Thatcher joined by members of her cabinet, also in Spitting Image-puppet form, this time captured through the lens of the photographers Andrew Bruce and Anna Fox.

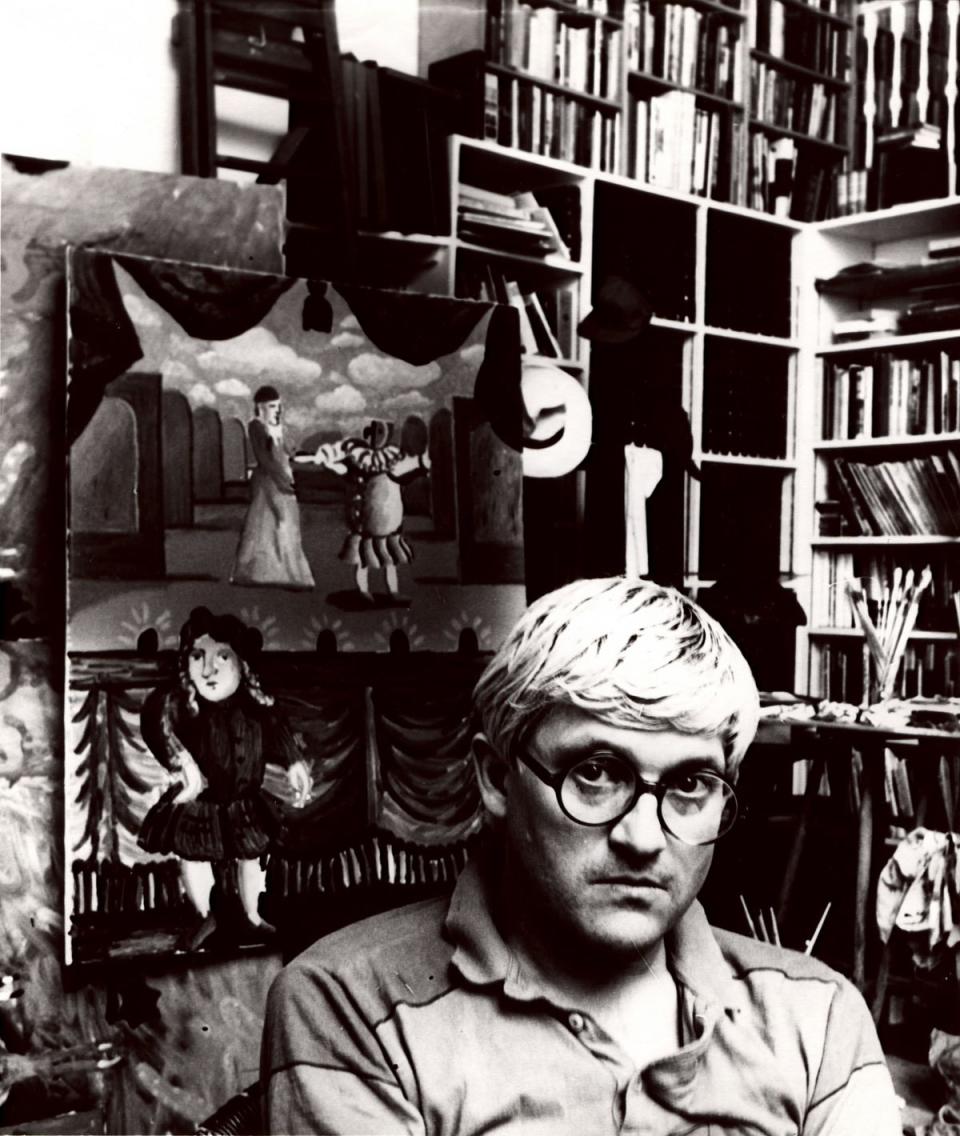

They’re here because the puppets, and more importantly the photographs, are part of the collection of James and Claire Hyman. The couple have been steadily amassing a major collection of British photography over a number of years – James, the center’s director, is also a dealer in British art, specializing in photographs.

The pair have been sharing their private holdings for some time, online at britishphotography.org and by lending works to exhibitions around the UK. But now they’ve created a permanent space with free admission, right in the heart of London, to do that – and much else besides.

There are marvelous things here. From clusters of photographs by important but underappreciated photographers like Joy Gregory and Maxine Walker, addressing race and place, to artists who are new to me, like Paloma Tendero, who draws ‘veins’ over her naked body using red strings, in a cumulative sequence of images. There are also pieces from Fast Forward’s project working with Rainbow Sisters – women from refugee backgrounds who identify as LGBTQ – in which they used photography as a storytelling tool.

James Hyman is keen to stress that while the center is focused on photography in Britain, “it’s not a nationalist view of British photography”. While you can visit and “get the greatest hits”, from Bill Brandt to Martin Parr (both featured in a superb display, The English at Home), the story he wants to tell is more complex.

“You can almost chart the changes in the nation through its photography, from a story that is very white and very male, to something that is much more diverse. There are many stories to tell now.”

When I talk to James, as he, Claire and their team are putting the finishing touches to the space, he’s keen to stress that the collection is only part of the story. “We actually want it to be a platform for other people to put on shows, maybe shows that are in the regions that wouldn’t otherwise get to London, or maybe getting outside curators and giving them a platform,” he says.

Cross the threshold of the gallery and this idea is clearly already in action with Headstrong: Women and Empowerment. It’s organized by Fast Forward, a research project directed by Anna Fox, which promotes women in photography, and features different forms of self-portraiture.

A group of ‘In Focus’ displays on the center’s first floor reflect the commitment to a breadth of voices and forms of contemporary photography. It’s fantastic to see a significant group of works by Jo Spence, the feminist photographer, themed around her thesis written as a mature student in 1982, which addressed the Cinderella myth. Here, Spence uses photography alongside text and collage, as a critical tool to reflect on gender and class stereotypes, in a Britain swept up in the royal wedding of Charles and Diana.

Nearby is a project by Heather Agyepong, where she explores the history of the cakewalk dance, its links to enslaved peoples and how they used it as a form of resistance. Agyepong reimagines the often offensive postcards of dancers distributed in Europe during the cakewalk craze of the early 1900s, with herself as a performer.

You couldn’t imagine a more different project to Agyepong’s than Natasha Caruana’s Fairytale for Sale, in which she has scoured the internet for hundreds of images of wedding dresses being sold, with the features of the brides cropped or blanked out, often crudely. Images intended to evoke romantic love become tainted and scarred; at best, a document of a commercial transaction, at worst, an emblem of broken lives.

Photography is scarce in London institutions – the Photographers’ Gallery is up the road in Soho, the V&A has one of the greatest collections of the medium anywhere in the world, and the Tate, after decades of ignoring it, now has holdings to be recognized with.

Hyman rightly says that the British focus makes it distinctive in the field. But, as the center’s deputy director Tracey Marshall-Grant suggests, there’s an increasingly “collaborative nature” among photography institutions.

“It all works together in a unified way,” he says, “with more access to photography, more opportunities and platforms for photographers, and more ways that people experience photography as an art form. We’re not trying to fill the gaps necessarily that other people aren’t [filling]. It’s more joined up: to do things in a better, bigger, more impactful way.”

The Center for British Photography opens on Thursday January 26; britishphotography.org